The car usage in the Netherlands

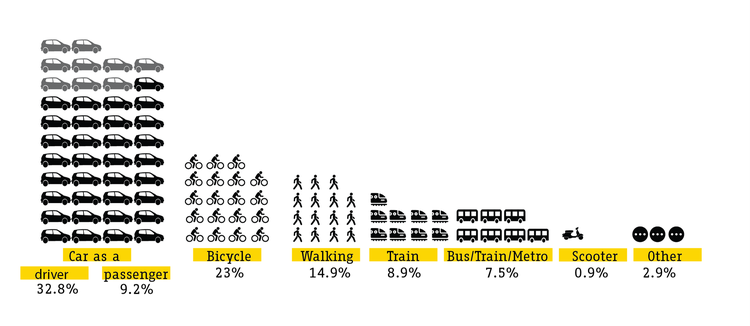

Private and motorized travel cause significant costs, Not only to actual drivers but also to society as a whole. These costs are, among others, environmental concerns, health impacts and time wasted in traffic congestion. In that sense, the idea of understanding what drives people to reduce car ownership and car usage and additionally explore potential alternatives has become highly relevant. Even though the existing public transport and bike infrastructure are of high quality, most trips in the Netherlands are mainly done in cars. In fact, according to the Netherlands Mobility Panel (MPN) in 2018, the main transportation mode for 42% of the trips was the car, either as a driver or as a passenger. The bicycle only accounts for around half of that amount. When looking at those trips in more detail, we see that 40% of them are shorter than 5 km., 23% are shorter than 2.5 km., and 9% are shorter than 1 km.

The situation in Amsterdam is different, but only to some extent. In fact, cars only account for 19% of the trips done by residents, whereas active modes and public transport account for the majority of the trips. However, there is a sizable number of car trips coming to the city from different areas of the country. In addition, interestingly enough, the travel distance of the car trips done by Amsterdam residents follows almost exactly the same distribution as the one in the entire country. Based on these figures, one could argue that 1 out of every 10 trips in the Netherlands are car trips that could potentially bike trips. Thus, what is missing? Is it exclusively because of specific personal barriers to using other modes? Or is there something else that makes someone lean towards acquiring and travelling by car?

Main transport mode share in the Netherlands (Source: Data from MPN 2018, graphic by SUM Team, AMS Institute)

Multiple dimensions of having a car

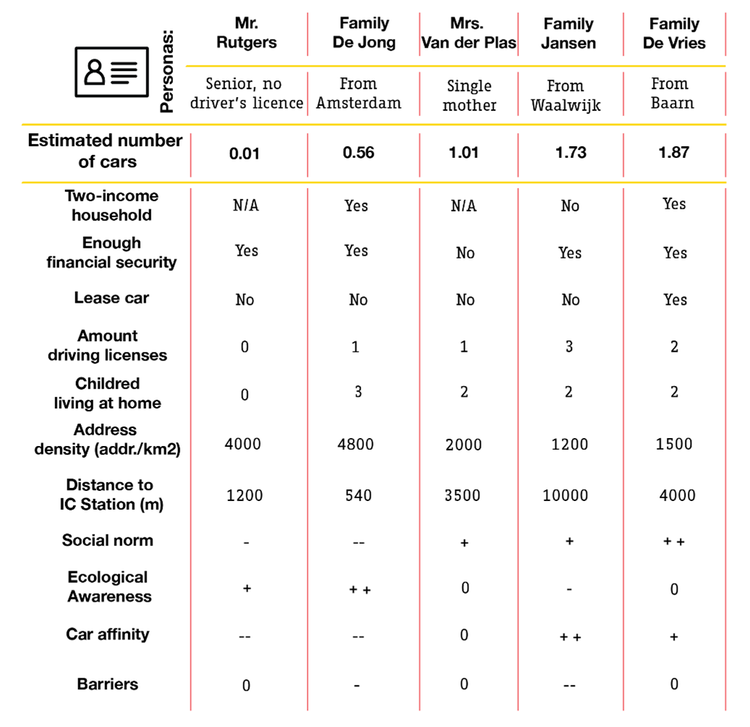

Typically, urban planners and transportation modellers consider travel times and costs when defining the appeal of different transportation modes. However, there are other dimensions that make a car “a car”. To this extent, the Netherlands Institute Of Transport Policy Analysis (KIM) recently conducted an analysis of the use of cars in the entire country. They focused not only on typical variables such as household composition and income, but they also considered residential characteristics and the role of certain attitudes. This type of analysis can be used to come up with different hypothetical groups, as in the figure below. For example, you can compare Family De Jong and De Vries who have different amounts of cars and also differ in their residential location (Amsterdam and Baarn) and their attitudes towards social norms, the environment, and the car. This type of analysis is relevant as it acknowledges that the car ownership phenomenon is a complex matter. In the following lines, I will sum up the results of an ongoing literature review I have been working on specifically on the matter of how, and to which extent, different attitudinal characteristics impact the decision to own and travel by car.

Determinant of the number of cars per household in five fictitious Dutch families (Source: Data/Idea from The Widespread Car Ownership In The Netherlands, KIM, reproduced by SUM Team, AMS Institute)

Car attractiveness

One of the most common dimensions studied is the one associated with the convenience a car represents in daily life. Frequent attitudes related are, for example, the freedom people feel in terms of using their car whenever they want with very little effort, the protection it gives when bad weather conditions strike, and how helpful they are when people need to carry on heavy burdens. In addition, there is the feeling driving a car produces in each person, which we refer to as excitement. Feelings of adrenaline, people enjoying the sound an internal combustion engine makes, the safe and personal space a car gives, and in general, all the positive emotions associated with the driving experience can be included in this attitude. It’s been seen in the literature that this particular attitude is positively correlated with being men and also with the younger groups of the population.

“Cars have a great impact on the use of space, safety, liveability and sustainability in cities. At the same time cities form the perfect place to move on foot by bike or public transport. At AMS Institute we explore how to reduce the impact of cars and help the transition towards a low-car city.”

Tom Kuipers

Program Developer

Societal consideration

Society also plays a role, which is actually bidirectional. First, there is the effect society has on an individual’s choice of owning and driving a car. This is referred to as the set of social norms. It’s very important to highlight that the effect of these societal norms depends on the context, as it has been observed differences between societies of different continents and also within the same global regions. Some typical examples are ideas like “buying a car is part of being an adult” or “everyone expects me to buy a car”. Second, there is the effect someone wants to make on society, which refers to the symbolic value the car gives. For many people, owning a car goes beyond the convenience perception but it is also a message they want to communicate. The type of vehicle, how luxurious it is, and thoughts about ‘what people will think about me if they see me with my car’ are the ideas around this attitudinal characteristic.

The role of the environment

Last but not least, the environment is present in the set of people’s attitudes, and it can be analysed in two different conditions: what refers to the natural and to the built environment. In terms of the natural environment, in the last decades there has been an increase in the presence of environmental concerns attitudes, which can be associated with a decrease in car use. However, the effect and more importantly the overall presence of this characteristic is still limited. In addition, people also consider the built environment when thinking about cars. For example, people lean towards different urban configurations, as having different urban density preferences, and enjoying (or not) pedestrian avenues and car-free zones. Notwithstanding, these dimensions are rather complex to study as it is different to separate the attitudes towards these characteristics and the residential location decisions.

From attitudes to decisions

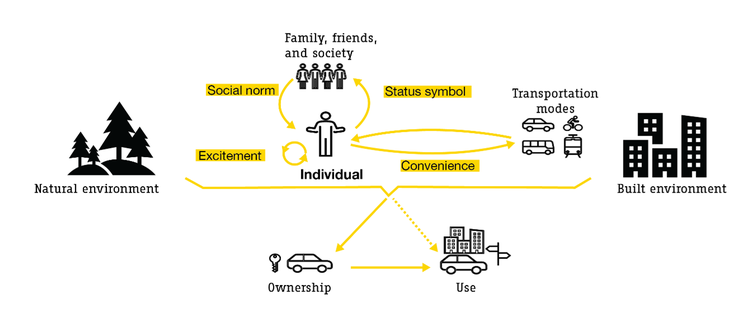

In the figure below you can see a diagram representing the individual’s attitudes towards different elements of the society and their influence over car ownership and usage. However, these characteristics are always relative to past experiences and individual contexts as they represent personal perceptions. For example, someone might consider that the car is the most convenient mode for their particular situation even when it might be significantly less affordable and other options, as ride sharing, might potentially serve the same needs.

Summary of different attitudinal dimensions regarding the decision to own and use a car (Source: Under review paper: Soza-Parra & Cats. The role of personal attitudes in determining car ownership and use: a literature review, reproduced by SUM Team, AMS Institute)

Final thoughts

Until a few years ago, it was necessary to first own a car to be able to move to any desired destination. Thus, most of the studies focus on this direction of things, analysing the effect on buying or owning intentions and then the effect on usage. However, two additional paradigms are present. First, it is not only attitudes that impact car ownership and usage, but also, using cars impacts the attitudes people have about them. Because of that, it is paramount to consider, on the first place, the effect car usage has in the attitudes people have towards cars and thus on the decision of owning one. Second, the massification of ride-hailing, ride-sharing, and car-sharing platforms is expected to affect the interaction of these attitudes and decisions. It is now possible to use a car and thus be benefited from all the perks associated with such a transportation mode without owning one in the first place. However, it is still to be answered to which extent attitudes like the status symbol will play a role in the usage of such alternatives. In addition, newer trends in car mobility, such as electrification and the addition of autonomous driving, with Tesla as a clear example, make the interaction of these different attitudes move in a still unknown direction. People with high environmental concerns, but also leaning toward projecting a status image with their transportation choices will be tempted by these new types of car alternatives.

“The complexity associated with car ownership and use motivation makes it hard to categorize car users. However, these analyses are paramount to understand better the extent different policies might have when attempting to reduce car use in cities. It will never be enough for some users to improve alternatives such as public transport, but it will require making using cars less appealing. Thus, policies such as free-car zones or no-car days, the reduction from 50 to 30 km/hr, and efforts to change existing norms, as in the case of “flight shaming”, are vital.”

Jaime Soza-Parra

Former Research Fellow at AMS Institute

The overall picture of the car ownership phenomenon is, as described, of complex nature. For a long time, it has been considered that offering better alternatives is enough to promote a shift from cars to more sustainable transportation modes as active travel and public transport. In a sense, this approach exclusively considers the convenience dimension, and only partly. People with strong feelings towards the excitement they get when driving and the status symbol the car represents to them will hardly ever consider other alternatives if they are just providing a better service. Other policy actions are then required.