For years, municipal mobility policies focused primarily on flow and efficiency. But anyone who does not own a car, cannot cycle or walk, or is unable to travel by public transport, has remained out of sight. Traditional traffic models often overlook these limitations. A new showcase from the Digital Orchestration of Public Space (DRO-DMI) program highlights this previously hidden group. It demonstrates how both qualitative insights and improved modeling can transform our understanding of transport equity.

To achieve transport equity, it’s essential to consider residents who are unable to fully participate in society due to limited access to suitable transportation. Traffic models are meant to help us understand mobility, yet they often oversimplify the reality they aim to represent. “Most models calculate mass movements across a city but fail to account for the people who don’t fit the norm”, explains Emma Schalkers (designer and researcher for the municipality of Amsterdam). “For example, residents who cannot cycle, who lack nearby facilities, or who simply move through the city differently from what ‘standard data’ shows. Our work highlights the gap between the output of standard traffic models and reality. By going out into the streets, observing daily mobility, and interviewing people with disabilities, low incomes, and other qualities that make their position more vulnerable. We discovered that data feeding current models often does not reflect the lived experiences of the community that policymakers try to support.”

“Talk to people. Observe the real world. Only by reconnecting data, models, and lived experience can we design inclusive mobility that genuinely serves everyone.”

Emma Schalkers (designer and researcher for the municipality of Amsterdam)

Missing bikes and bus stops: seeing the gap

Transport equity requires more than just better infrastructure or faster connections. It’s about understanding people’s real abilities, vulnerabilities, and the daily trade-offs they face. “To do this, cities must start with people”, emphasizes Schalkers. “What do we want to learn? What do residents need? This helps determine which data and variables are most useful for their local context.”

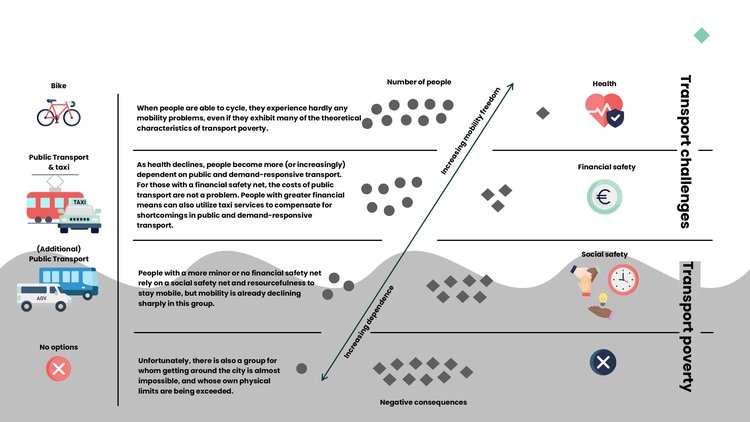

The conversations with residents reveal that being able to cycle is often essential for staying mobile in the city. Those who can no longer cycle become dependent on public transport or taxis. Options that are expensive, less accessible, and sometimes unreliable. “Small groups without a financial and/or social safety net experience the heaviest, and often invisible, consequences”, explains Gerry de Koning (Smart Mobility program manager at the municipality of Almere). “For these residents, the disappearance of a bus stop is not just an inconvenience: it can limit access to healthcare, meaningful social contact, employment, or education.”

Framework to distinguish suboptimal transport options and transportation poverty

A survey among low-income residents in Flevoland revealed that 11 percent of people are unable to cycle, 18.8 percent are unable to walk for more than 10 minutes, and 10.4 percent are unable to travel independently using public transport. Without these variables, traditional traffic models paint a distorted picture of what is reachable and which neighborhoods are well-connected. The lesson is clear: do not become blind to the world outside the model. “A model is always an approximation”, adds Schalkers. “Layering model upon model only moves us further from what truly matters to residents, obscuring the elements most relevant for transport equity.”

A new model for transport equity

DRO-DMI collaborated with Goudappel to integrate new characteristics into their microsimulation model, Octavius. This includes cycling ability, walking ability, and independent use of public transportation, as determined by the survey conducted in Flevoland. “By paying more attention to the possibilities and limitations of walking and cycling, we gain a much more inclusive view of mobility”, says De Koning. “Some cities are already taking this approach, integrating richer datasets into their own systems or testing this new model.”

The new model allows municipalities to make targeted policy decisions. For example, in Almere, the model serves as a second opinion. If a public transport line appears underused and is proposed for cancellation, this model can reveal how many people would lose access to essential services. This allows municipalities to reconsider decisions or explore alternatives for more inclusive policy. “Even small interventions can matter”, adds De Koning. “Some residents cannot reach a bus stop without taking breaks along the way. Adding a few benches can mean the difference between staying home and participating in society.”

“Even small interventions can matter. Some residents cannot reach a bus stop without taking breaks along the way. Adding a few benches can mean the difference between staying home and participating in society.”

Gerry de Koning (Smart Mobility program manager at the municipality of Almere)

How to Advance Transport Equity in Your City

The call to action is straightforward: understand which data is used in a model. Who is missing? And what assumptions shape its outcomes? “And above all: go outside”, advises Schalkers. “Talk to people. Observe the real world. Only by reconnecting data, models, and lived experience can we design inclusive mobility that genuinely serves everyone.”

Contact

Interested in our survey to get your own data? Or in testing of integrating this updated traffic model? Please get in touch with https://dro-dmi.nl/contact/

Award-winning papers

The two research papers (a collaboration between Amsterdam, Almere, and Goudappel) on which this showcase is based both won awards at the CVS conference. The paper ‘Een menselijke kijk op vervoersarmoede’ (Schalkers et al, 2025) shows, through powerful qualitative research, how losing the ability to cycle or walk can push people into deep mobility disadvantage, often invisible in traditional data. The second paper, ‘Vervoersarmoede in beeld brengen met een verkeersmodel’ (Voorhorst et al, 2025), demonstrates how integrating real abilities, such as cycling proficiency, walking limitations, and independent public transport use, into a microsimulation model significantly enhances the visibility of ‘vulnerable’ groups. Together, these studies demonstrate a groundbreaking showcase: combining lived experience with advanced modelling to build more just and inclusive mobility policies.

Check our booklet about the ‘Showcase Vervoersarmoede’ (in Dutch)